Physics For Scientists And Engineers 6E - part 259

1033

Alternating Current Circuits

C H A P T E R O U T L I N E

33.1 AC Sources

33.2 Resistors in an AC Circuit

33.3 Inductors in an AC Circuit

33.4 Capacitors in an AC Circuit

33.5 The

RLC

Series Circuit

33.6 Power in an AC Circuit

33.7 Resonance in a Series

RLC

Circuit

33.8 The Transformer and Power

Transmission

33.9 Rectifiers and Filters

▲

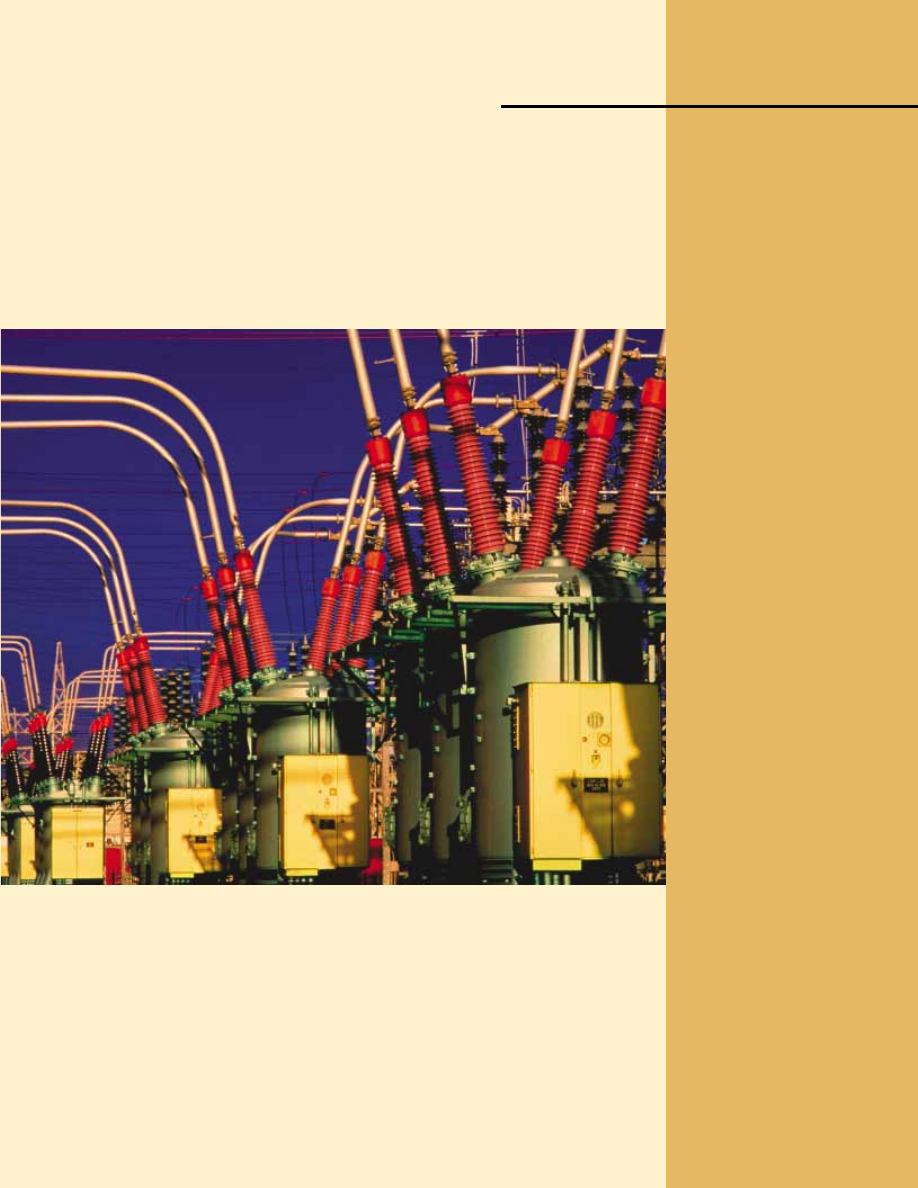

These large transformers are used to increase the voltage at a power plant for distribution

of energy by electrical transmission to the power grid. Voltages can be changed relatively

easily because power is distributed by alternating current rather than direct current. (Lester

Lefkowitz/Getty Images)

Chapter 33