Physics For Scientists And Engineers 6E - part 239

SECTION 3 0.9 • The Magnetic Field of the Earth

953

Estimate the saturation magnetization in a long cylinder of

iron, assuming one unpaired electron spin per atom.

Solution The saturation magnetization is obtained when

all the magnetic moments in the sample are aligned. If

the sample contains n atoms per unit volume, then the

saturation magnetization M

s

has the value

where # is the magnetic moment per atom. Because the

molar mass of iron is 55 g/mol and its density is 7.9 g/cm

3

,

M

s

"

n#

Example 30.11 Saturation Magnetization

the value of n for iron is 8.6 & 10

28

atoms/m

3

. Assuming

that each atom contributes one Bohr magneton (due to one

unpaired spin) to the magnetic moment, we obtain

This is about half the experimentally determined saturation

magnetization for iron, which indicates that actually two

unpaired electron spins are present per atom.

8.0 & 10

5

A/m

"

M

s

"

(8.6 & 10

28

atoms/m

3

)(9.27 & 10

'

24

A(m

2

/atom)

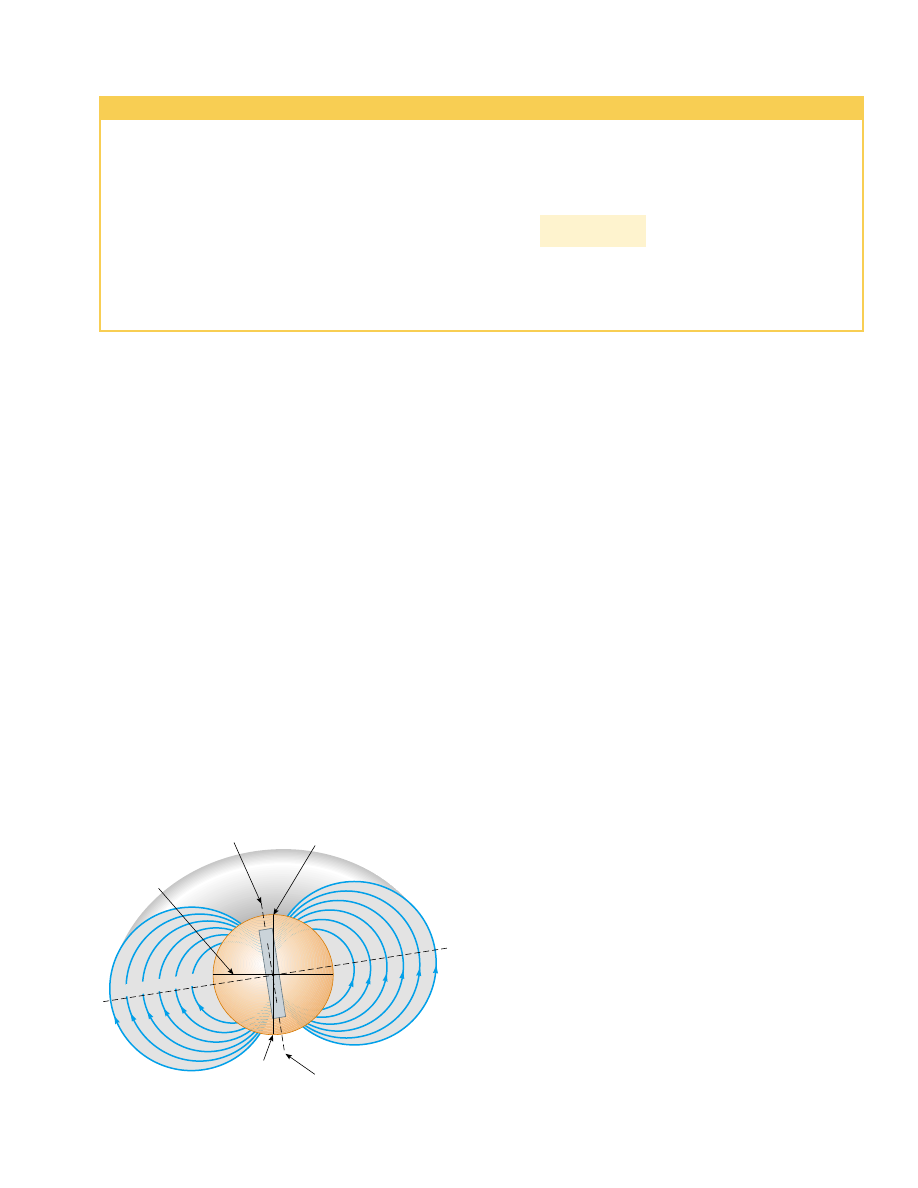

30.9 The Magnetic Field of the Earth

When we speak of a compass magnet having a north pole and a south pole, we should

say more properly that it has a “north-seeking” pole and a “south-seeking” pole. By this

we mean that one pole of the magnet seeks, or points to, the north geographic pole of

the Earth. Because the north pole of a magnet is attracted toward the north

geographic pole of the Earth, we conclude that

the Earth’s south magnetic pole is

located near the north geographic pole, and the Earth’s north magnetic pole is

located near the south geographic pole. In fact, the configuration of the Earth’s

magnetic field, pictured in Figure 30.36, is very much like the one that would be

achieved by burying a gigantic bar magnet deep in the interior of the Earth.

If a compass needle is suspended in bearings that allow it to rotate in the vertical

plane as well as in the horizontal plane, the needle is horizontal with respect to the

Earth’s surface only near the equator. As the compass is moved northward, the

needle rotates so that it points more and more toward the surface of the Earth.

Finally, at a point near Hudson Bay in Canada, the north pole of the needle points

directly downward. This site, first found in 1832, is considered to be the location of

the south magnetic pole of the Earth. It is approximately 1 300 mi from the Earth’s

geographic North Pole, and its exact position varies slowly with time. Similarly, the

north magnetic pole of the Earth is about 1 200 mi away from the Earth’s geographic

South Pole.

Figure 30.36 The Earth’s

magnetic field lines. Note that a

south magnetic pole is near the

north geographic pole, and a

north magnetic pole is near the

south geographic pole.

North

geographic

pole

South

magnetic

pole

Geographic

equator

South

geographic

pole

North

magnetic

pole

N

S

Magnetic equator